The Puppy Movement: CPTED & a New Vision for Security

When designing inhabited space to mitigate unwanted behaviors, we must embrace nonelectronic, nonaggressive technologies.

When we think of security, we often think of products. We think of fences with concertina wire on top, big bold cement blocks, or at the very minimum a jersey barrier to prevent vehicular threats. We think of armed soldiers walking the streets in Europe and stationed in “places of interest” here in major U.S. cities and in places like Times Square or Union Station. At sporting events and outdoor concerts, we think of metal detectors and bag searches. And when traveling, we think of bag searches, emptying pockets or standing for a body scan.

These mechanisms are designed to be very visible. They’re almost designed to be “in your face.” They are saying, “Hey, scumbag come over here, and we’re going to get you. So just try us!”

And there are also the electronic systems like cameras or biometrics and a whole slew of other technologies that add to a “Big Brother is watching” feeling, almost as if we’re in a war zone and are expecting an attack by the hordes at any minute. I call this type of security implementation the “Big Dog” concept.

It’s like the big black and white sign with red letters on the garden gate that warns of a big slobbering Rottweiler on the other side of the gate just waiting to “take a bite out of somebody.” It’s bold and in your face on purpose – like John Wayne slinging his side-arm. But this Big Dog attitude and the big woof that goes with it really doesn’t do much in the way of preventing bad things from happening. It transfers some of the threat likelihood to somewhere else. But most of the time, a dedicated threat will not be deterred. The “bad actor” only brings a bigger, better ladder or bolt cutters or a gun to the party.

The real value with all this physical security lies in the fact that it helps distinguish good behavior from bad. After all, that’s security in a nutshell, isn’t it? Reward good – deny bad. Good behaviors are those actions that people can do and we reward them for it. For example, if you have the right debit card and PIN at the ATM, the machine will give you your money; bad behavior, on the other hand, stolen debit card or wrong PIN and no money is dispensed.

A Place for Big Dog

Now that said, there is a place for the Big Dog, but not in every circumstance or in every occasion. One of those circumstances involves uniformed armed security forces on-site. Having security forces on-site allows for immediate intervention when the normal good behavior is just slightly off – for example, when an employee forgets their access badge at home. A guard can look them up in the database and allow temporary entry.

Now that said, there is a place for the Big Dog, but not in every circumstance or in every occasion. One of those circumstances involves uniformed armed security forces on-site. Having security forces on-site allows for immediate intervention when the normal good behavior is just slightly off – for example, when an employee forgets their access badge at home. A guard can look them up in the database and allow temporary entry.

This is a good thing and is the best argument for having a guard force. Their real value comes in their ability to assess and decide the right course of action when things are off.

The reliance on physical security engineering will become paramount as we use inhabited space to mitigate unwanted behaviors and reduce its effects. We cannot lose sight of the human aspect of using new technologies as we move forward. The use of invasive technologies will need to give way to nonintrusive technologies. We want users of the space to do the right thing because it’s the right thing to do, not because “Big Brother” is watching them. This will take time. But there’s no better time to start than now.

A Change Is Afoot

As the great migration from the countryside to urban centers becomes an increasing phenomenon, community leaders must meet the challenges that lie ahead. As systems of urbanization become ever-more complex, so will the solutions to resolve the problems they cause. Cities are becoming more and more complex. The systems they incorporate are being evermore intertwined. There is no such thing anymore as an independent system.

And the collection of data has evolved into a business vertical itself. As connectivity to the Internet of Things (IoT) becomes the norm, so will the need for other types of technologies that are not relying on this connectivity. We saw what happened recently during Hurricane Maria. Loss of the electric grid had catastrophic results, from which people are still recovering. I imagine that in the future, every electronic gadget will have self-sustaining power, but we are a long way from that now. So, in the meantime, we should concentrate on nonelectronic solutions. It’s imperative that not only will smart cities be highly functioning and efficient but they must also be – first and foremost – safe.

It will require good infrastructure systems, good inhabited space design, good governance and good community involvement. The right mix of technology from all sectors and behavioral sciences will be needed. Due to this holistic approach to city planning, companies wishing to compete in this space will need to bring in a variety of specialties to adequately meet the consumer’s needs. As an example, inhabited space design cannot be a function of only architects and engineers. It must also include security professionals, transportation experts, government officials, behaviorists and community members, both retailers and residents.

It will require good infrastructure systems, good inhabited space design, good governance and good community involvement. The right mix of technology from all sectors and behavioral sciences will be needed. Due to this holistic approach to city planning, companies wishing to compete in this space will need to bring in a variety of specialties to adequately meet the consumer’s needs. As an example, inhabited space design cannot be a function of only architects and engineers. It must also include security professionals, transportation experts, government officials, behaviorists and community members, both retailers and residents.

Research is showing us that we can create environments that reduce crime by using a variety of “social behavior engineering mechanisms.” I hate to use the words “manipulating behavior,” but that’s exactly what is happening. All large electronics companies and very large retailers are using your data, which you willingly agreed to provide when you signed a user agreement, so that they can harvest your behavior to their advantage. In the end, they want to get your money.

Good Stewardship

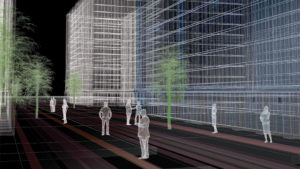

City planners, building designers and others involved in developing mitigation strategies will need to embrace other nonelectronic, nonaggressive technologies. One of those technologies is the use of Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED) principles in the development of neighborhoods.

The concept of CPTED has been around since the ‘90s and is an effective approach. Communities that use CPTED principles tend to thrive economically and socially. The social engineering of the built-environment can be taken even further. Research is being done in Eindhoven, The Netherlands, to track a person’s movement throughout a pedestrian zone by analyzing which “smells” a person is subjected to as they move through the space. Why do people park in one parking garage and walk all the way over there to get a sweet or why does a person stop and have a cigarette on that park bench? In Melbourne, Australia, a recently installed art project tracks a person’s movement through a simulated ocean to see its effect. The more movement, the more the whirlpools in the ocean are affected. This “interactive art” tells us something about social behaviors.

Recently, architect Stefano Boeri was cited by Dezeen Magazine as saying, “Cities should be redesigned to include trees with bulky planters rather than concrete barriers to prevent vehicle attack.” He went on to say, “A big pot of soil has the same resistance as a Jersey (modular concrete barrier), but it can host a tree – a living being that offers shade; absorbs dust, CO2 and other subtle pollutants; and provides oxygen and a home for birds.”

He’s right. No one wants to sit at an outdoor café sipping their cappuccino while looking at big concrete blocks that make them feel like they’re in a war zone. Environments that are a mixture of color and natural materials are much more soothing and aesthetically pleasing. They give us that “puppy dog” feeling – the feeling that you get when you cuddle a puppy. You feel safe and protected.

Creating the “Puppy” Environment for Everyone

It seems crazy to me that in some neighborhoods, we allow crime and others we don’t. It’s almost as if we’re saying, “You can be bad over there, and we don’t care. But over here you have to play good.” That’s just wrong! Every neighborhood needs to be safe. Every kid deserves to grow up in a neighborhood that provides opportunities for growth. But parents can’t do it alone, we must help them. We must insist that neighborhoods are designed to prevent or deter crime in all its forms, including radicalization – whether ideological or sociological.

The use of concepts such as CPTED must be applied to all neighborhoods. The presence of physical security measures in the form of aggressive electronic solutions must give way to nonelectronic countermeasures that are nonaggressive. They can go a very long way in creating an aesthetically pleasing built-environment.

Criminologists are looking at a variety of mental health issues that affect behavior. After all, criminal behavior, including terrorism, is a type of unwanted behavior in a peaceful society. Some of those influences are long term and build up over the years of physical and mental abuse, while others are short term. In any case, psychology is a main factor in why people do what they do. Shouldn’t we use them to our advantage and combine social behavior with the engineered space so that they both work together and in fact, complement each other?

When people feel safe in a space, they tend to use it more. When security is a “tax” or burden, people will either avoid the space or figure out a way to circumvent the security solution. Being cumbersome is a delay mechanism that we should use to assist us in assessing behavior – and that is useful on its own. The problem comes from the frenetic pace of today’s society. In short, people don’t want to be bothered.

When people feel safe in a space, they tend to use it more. When security is a “tax” or burden, people will either avoid the space or figure out a way to circumvent the security solution. Being cumbersome is a delay mechanism that we should use to assist us in assessing behavior – and that is useful on its own. The problem comes from the frenetic pace of today’s society. In short, people don’t want to be bothered.

The use of colors, a variety of natural building materials, water, lighting and even a meandering sidewalk all add to the “puppy” movement. That’s the feeling we should be striving to achieve as we design security into the environments of the future.

Doug Haines (doug@hainessecuritysolutions.com) is the owner of Haines Security Solutions (hainessecuritysolutions.com).