Security Convergence 2024

About the Report

Since the first security camera was placed on an IT network, convergence has been talked about in our industry. For some, convergence has meant connecting technologies from physical security and IT, and for others, it means connecting cybersecurity, information security and physical security strategies.

At the Security Industry Association (SIA), we have closely followed the theme of convergence, as it impacts both our practitioner members and the technologies delivered by our manufacturer and integrator members. This convergence of physical security and cybersecurity continues to progress and has led SIA to invest in and develop resources to help our industry adapt to convergence, with efforts including operation of the Cybersecurity Advisory Board, which provides insights and resources in this foundational area; the Security Industry Cybersecurity Certification (SICC), the industry’s first credential focused specifically on cybersecurity for physical security systems; interactive trainings, conference sessions and webinars focused on key cyber-physical security topics; conversations around convergence in the annual Security Megatrends report; and the creation of resources like product and system hardening guides, cybersecurity onboarding recommendations and more.

Convergence, while a buzzword for decades in our industry, has sometimes been slow to produce results and may look different now than we originally envisioned, but in the coming years, true convergence may finally become inevitable, as the networking of security devices and the increasing integration of security into other technologies could make silos not just inefficient, but impossible. In this SIA report, we’ve worked to distill where convergence is at a moment of change, provide some history on the concept and offer some future perspective.

Table of Contents

-

Looking Back and Moving Forward

In the past, interpretations of the topic of “convergence” were based on infusing technologies together, resulting in a new concept – or even a specific product offering. Did the industry get it wrong? Fast forward, and adoption hasn’t quite matched enthusiasm of the original vision most in the industry held.

Time bestows the benefit of retrospection, and this paper details how the concept is actually flourishing, but in different, broader and more meaningful ways than originally anticipated. It also explores why convergence has evolved, as well as its application and impact within the physical security industry. Actionable steps will be outlined to provide insight into best practices in considering, investigating and applying concepts that are covered.

Postmortem

Analysis of how convergence was promoted and applied in the past reveals that despite the topic being novel, concepts that were presented fell short on value, were too challenging to execute or both.

Perhaps one underlying cause was there was no clear universal definition of what “convergence” was. Ask 20 different security professionals, and they’re likely to provide as many different answers. Understandably, there was a bit of confusion. Manufacturers weren’t short on perspectives, and they provided a surrogate function to what convergence was. They were often hyperfocused on integrating technologies and delivering some operational and security improvements but inevitably struggled to get funding because the business case just wasn’t compelling enough, as they delivered limited benefit to the greater organization and presented significant operational challenges.

Most concepts were new and required collaboration with resources outside of physical security, management support and additional skills than had been projected. Coordinating, refocusing and reallocating resources that were already committed to their existing functions were significant barriers.

If organizations got past the first two challenges, they encountered cultural and political obstacles. IT and physical security had been separated for so long that not only were their systems siloed apart from one another, but also their technologies, standards and policies were drastically different. Convergence requires harmonizing these aspects as a prerequisite to effectively plan, execute and maintain.

Ultimately, many organizations either didn’t have the appetite to provide the level of transparency required for the efforts, relitigate significant portions of their security programs or work through the significant political aspects that eventually became apparent.

Revisiting the Concept

Despite the shortcomings of its original premise, in recent years convergence has been flourishing — but in different ways than originally anticipated. By all accounts, it’s more relevant to end users and compatible with their current challenges and objectives.

Modern Convergence Projects That Involve Broader Objectives

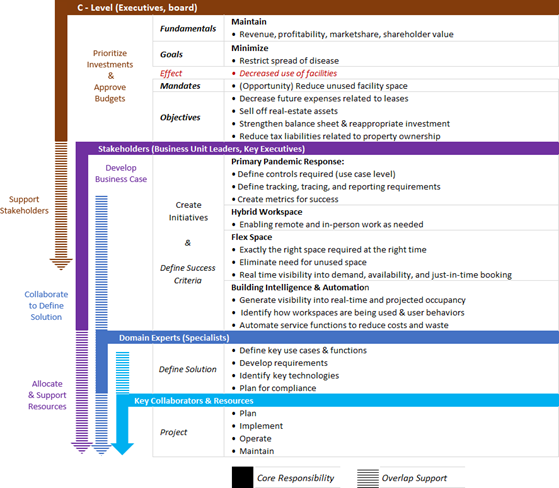

Rather than being driven by industry and defined by specific offerings, convergence is being undertaken by end users whose organizations are determined to achieve specific outcomes that are at higher priority levels which can’t be achieved in isolation from other systems, people and departments. Often, such initiatives may represent achieving a prioritized business directive which isn’t owned by physical security yet is identified as a critical component in the solution to the desired outcome.

For example, at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, many organizations experienced urgent demands by their executive management to redirect focus away from planned security projects and collaborate with other departments to achieve on-site attendance metrics, people tracking, wellness visibility, contact tracing and specific controls for compliance and reporting. This shift was purely a business demand that didn’t impose a security outcome but rather required a great deal of engagement with stakeholders and collaboration with other departments to jointly determine a viable solution, fuse intelligence and reengineer some processes to achieve success of a business outcome.

Operational technology (OT) is another area where convergence is becoming commonplace for organizations that rely on industrial control systems (ICS). There are various classes of ICS which serve as the backbone of many organizations’ critical infrastructure across a variety of industries. These systems fulfill a broad range of purposes, such as water and sewage treatment, pharmaceutical manufacturing, automotive manufacturing, chemical plants treatment, traffic signal controls, natural gas networks, electrical grids, pipeline systems, satellites and transportation.

The prospect of ICS being compromised represents a massive impact to an organization’s operations and revenue and the safety of their customers (and communities they serve). Stopping bad actors at the network level alone isn’t adequate. In fact, many ICS are older, predating the internet, but still serve their intended functional purpose and are too expensive to replace. Whether organizations are planning to upgrade their ICS or not, executives continue to increase priority on business continuity and resiliency, which requires in-depth physical controls to prevent noncompliant activities across a range of both bad actors and authorized personnel alike. In order to design meaningful controls, physical security professionals need to work with business managers, ICS engineers and risk managers to understand specific uses cases and determine what is noncompliant, otherwise such controls will be more generic and less effective.

Increased Demand for Physical Security to Play a Larger Role in Other Departments

On other fronts, departments executing their own objectives are experiencing increased needs relating to physical security. For example, the number of compliance mandates continues to increase, with many evolving to recognize that implementing controls to prevent noncompliant use or unauthorized access to systems over the network isn’t adequate without also requiring commensurate controls over actors that may contemplate physical access to those systems or the adjacent environments that can provide a unique vector as an alternate path to success (e.g., the ability to do social engineering more effectively from within or gain physical access to one system and traverse to another from a route that has fewer barriers).

It is not uncommon to see scenarios where a pharmaceutical lab needs high levels of assurance to prevent espionage of IP, contamination or safety events from occurring.

Many organizations are upgrading their data center security to increase resiliency and meet increasing compliance measures that require physical security elements (e.g., SOC2, PCI DSS and even the nascent CMMC 2.0).

While some colleagues know the business process well and others respective cybersecurity aspects, neither are physical security experts. There is increased recognition that their participation and assistance are needed to meet higher standards being set to achieve their own objectives.

Physical Security Is Thinking Bigger

Not to lose sight of the fact that all the while, physical security executives still have their own department-level challenges and improvements to make, there is more pressure now than ever before to demonstrate transformational outcomes in a business case to get funding appropriated for the effort.

The days of getting funding approved for iterative system upgrades, improving processes that those external to security won’t experience or reducing risks that can’t be measured or effectively articulated to be a priority to the business are in the rear-view mirror for most. But that doesn’t mean security professionals are taking it lying down – on the contrary. Security leaders have been tuning in to how other departments are able to get funding, the level of innovation being incorporated and elements of the business case that need to be included.

The range of use cases are varied and mounting yet appear to share a common denominator where security leaders are changing how they engage with other functions within their organization. They are shifting from calling on colleagues in adjacent departments (such as information security (InfoSec) to advise on their own projects (typically as an approver function, such as guidance or assistance with network requirements) to soliciting what their top priorities are and identifying opportunities to build in capabilities that may provide benefits to them as well.

For example, a project slated to improve situational awareness within physical security might also provide some intelligence value to other departments as a byproduct to increase value to the organization, and as a result the business case is stronger and support for resources becomes more likely, particularly if that other project reflects an outcome that is already a high priority with executives. This isn’t limited to specific technology functions but rather is unlimited across the rest of the organization, whether it’s workplace management, real estate, manufacturing, research and development or otherwise.

The fact of the matter is, wherever people physically are engaging with organizational assets and operations that are critical to the business, there exist elements of physical security that either are being overlooked or represent an opportunity for improvement.

Importance of Observing This Topic

For years, physical security has operated in a silo, and not necessarily always by choice. Technology developed apart from IT systems disparate from one another, and personnel were allocated specifically to manage these unique aspects – so too was the management structure to support it. Over time, core principles, methodologies and practices of physical security were uniquely different than their IT counterparts.

Just get physical security and information security teams in a room to talk about “key management,” and it might take 20 minutes for each side to realize that one side was referring to physical keys to open locks and how best to manage access to them while the other was thinking only about encryption keys and how best to distribute and manage them across devices.

Many physical security leaders found some success in being less encumbered by oversight to make autonomous decisions. Arguably, this fueled the status quo of separation. However, a more recent trend is that the same security leaders (or the next generation that inherited their programs) are often finding the silo that had been built is becoming more its own island of aging infrastructure, limited resources and trying to figure out how infuse modern resources afforded other departments that had long ago made the move to the mainland.

Ironically, many security leaders were around when InfoSec was stuck on the “basement” and witnessed their transformation to being well supported board room participants. More broadly, InfoSec isn’t unique, as other departments have gone through similar evolution successfully. It’s fair to say many physical security leaders express their desire for a similar shift.

For the most part, whereas convergence of the past was asserted by solution providers as a “destination” (acquiring a specific capability or obtaining specific state), security leaders are demonstrating that it’s rather an “exercise” of broader collaborative engagement, shared incentives and harmonizing practices so all participants have a realistic path for execution – an important remedy to where previous convergence concepts fell short.

Timeliness of Topic

There is increased pressure on physical security leaders to address an expanded portfolio of threats while operating expenses (OpEx) budgets are at maximum utilization, with little appetite from executives to increase either OpEx or capital expenditures (CapEx) to address them; however, there are pathways to success. As the threat landscape evolves and expands, so do the range and gravity of risks that executives need to address. Ultimately, executives fund risk remediation, not security. Increased corporate governance requirements, regulations and liability mean that owning risk and making decisions can’t be avoided.

Many security leaders struggle with designing an initiative that touches the core priorities of executives and compels them to fund what is being proposed.

Convergence as an exercise will facilitate discovering those priorities, identifying stakeholders to collaborate with and initiatives to be part of, but physical security also needs the tools to deliver.

In the past, the industry as a whole wasn’t set up to facilitate big crossdepartmental ideas; however, the physical security industry is undergoing arguably the most significant transformation in its history. The undeniable influx of advancing technology becoming available provides a unique opportunity to achieve things that previously weren’t possible or do them in ways that are more efficient and extremely compelling.

Certainly, physical security leaders should exercise efforts to explore how these compelling advances can shift the paradigm for their programs ranging from projects that have a completely new profile to old challenges being solved in new ways; however, convergence also represents new challenges.

Most of the technological advances are areas where physical security end users have little experience, expertise and resources to get a handle on the capabilities, requirements and risks of employing them in the first place. This can quickly turn opportunities into cybersecurity liabilities or privacy violations or risk the project’s overall success in being rolled out and appropriately managed, yet there are steps within a convergence model that end users can take to address these risks and accelerate adoption and success.

Outlook

The End-User Journey Is Continuous

Convergence is occurring across a number of end-user programs and achieving different types of outcomes that change perception from being seen as a cost center to as a key contributor. Each convergence project brings together a variety of stakeholders, perspectives and new possibilities which in time brings into consideration changing specific practices, modifying operations or redesigning more fundamental aspects of the security program itself.

Convergence Will Continue to Be Defined and Redefined by End Users

End users have significant responsibilities of running security programs that span several specialized capabilities. They have the responsibility to ensure success and the burden of failure if things don’t work out. As end users exchange ideas around similar challenges, socialize their success and share best practices, certain approaches become common within the industry, while others require further consideration by few to solve it for the many (who might not be as aggressive or adventurous or have as many resources at their disposal).

All Constituents in Industry Will Be Impacted in Various Ways

As early adopter end users experience transformative outcomes through convergence and identify key elements they require, manufacturers will play a critical role in productizing solutions that can commoditize the implementation, accelerate time to value and reduce project risk. Manufacturers and respective channels will need to understand the nature of these demands and adjust their offerings, reconsider where they specialize and how they engage with perspective customers to support their revised objectives.

New Entrants Into the Market

An outsized trait of convergence is the pursuit of taking on big challenges and solving them in bold, innovative ways that result in more meaningful outcomes. A big part of innovation is reserving high expectations and an open mind as to who can fulfill them.

The range of technologies that are well-positioned candidates to be major catalysts in this equation – such as artificial intelligence (AI), mobile, cloud and sensors – aren’t inherent to the physical security industry. They need shape, purpose and expertise to be packaged and consumed. Interestingly, all these technologies (and others) are new to physical security but not necessarily to other industries. There exist two potential arguments where both could be true:

- Manufacturers within the industry collectively need to play a bit of catch-up in harnessing and assimilating these new technologies into something that is compelling and can be delivered to their

- It could be argued equally that manufacturers from other industries who already successfully specialize in these areas could use their existing intellectual property, core resources and expertise to expand into physical security as a new opportunity for them (and may share the same customers, hence not entirely be “outsiders”).

There exists a range of possibilities that could occur. For example, industry incumbents could embed AI into their existing product or a company that specializes in AI could develop hooks into physical security systems to make more compelling use of the data – both scenarios are actually currently playing out.

Cybersecurity Continues to Elevate to the Board Level – Pulling Physical Security Along With It

As physical security technology increasingly becomes indistinguishable from those employed by IT, the same cybersecurity risks are inherited and need to be addressed. The industry has been acclimating to this realization for the past few years.

In July 2023, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) adopted new rules to enhance and standardize disclosures regarding cybersecurity risk management, strategy, governance and incidents by public companies that are subject to the reporting requirements of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (the “Exchange Act”).1 At a very high level, the rules require any publicly traded company to file disclosures with the SEC (via Form 8-K) concerning cybersecurity incidents that are determined to have material impact on the company (and investors), including the timing, scope and nature of the incident. The Exchange Act also requires annual disclosure of cybersecurity risk management, strategy and governance (via Form 10-K).

Both of these requirements are significant material steps for advancing cybersecurity into the hearts and minds of corporate governance, but the second part is particularly interesting, as it includes companies to disclose their processes for assessing, identifying and managing material risks from cybersecurity threats. Companies are also required to describe board of directors oversight of risks from cybersecurity threats and identify board committees and subcommittees that are responsible for oversight and management’s role in assessing and managing material risks from cybersecurity threats.

Translation – for any publicly traded company registered with the SEC, cybersecurity is no longer a “best effort” of placing bets through bullets gleaned by inviting IT up to the board room for occasional briefings. Rather, it holds executive management accountable to take ownership of risk and ensure there is process and capacity to facilitate continuous awareness, assessments and truthful reporting as they would with do with other aspects of their 10-k.

It’s conceivable if not predictable that if organizations haven’t already elevated the CISO role to be part of the executive team and inclusive in ongoing board activities, they are likely to do so quickly as reporting is required to start for fiscal years ending on or after December 2023.

Now the big question, if physical security systems are becoming indistinguishable from IT systems, inherit similar threat profiles, are cybersecurity risks of physical security systems excluded from these obligations? Consider that anytime physical security systems are integrated with other systems across the enterprise that do fall into this area (essentially every other system in the organization from financials to manufacturing to sales and marketing). Anything that is connected represents a potential vector for initial attack and parallel movement to another system toward the ultimate target. This is how targeted attacks work – the type of attacks that would likely meet the requirement for “material impact” and necessitate reporting.

It will be interesting to see how chief information security officers (CISOs) will view the evolution of physical security systems and whether they’ll treat them like any other connected system with similar attack surfaces and vulnerabilities. Further, once they recognize the physical security industry’s ongoing cybersecurity dilemma of trying to catch up, will they acquiesce to traditional separation or impose a more formal relationship to ensure 10-k compliance?

It will take time to get some definitive answers, but it’s at least likely that physical security shifts from the peripheral view of a facilities function and is thrust right into the executive compliance fold. Physical security will be an equal part of a common incentive model that is instituted at executive levels for all business, security and risk stakeholders to work together, align objectives, coordinate resources and harmonize practices. At minimum, it’s starting to sound a lot like convergence taking shape.Modern Convergence

This section will outline the modern definition of convergence, analyze the broader organizational dynamics that help shape it and examine how various components influence one another.

A New Reality

Convergence got a big push about 20 years ago in the physical security industry.

Notwithstanding how it played out, much has changed since then, not only within the industry but also inside the greater business environment it endeavors to protect.

In that time, enterprises have transformed their operations to become mostly digital, implemented business intelligence and expanded automations, resulting in higher efficiency, agility and speed at which they operate. At the same time, technology within physical security has made significant advances, yet most end users’ infrastructures are aging and increasingly experience challenges gaining adequate funding to take advantage of such advances.

Meanwhile, the scope of threats has only expanded, and the complexity to implement countermeasures, technology and employ more specialized resources to execute has become significant a challenge for physical security leaders. Engaging with executives on this premise might win some sympathy but seldom translates to tangible support that’s requested.

The hard fact is that physical security leaders compete with the rest of the organization for funding. Many security leaders struggle with being perceived as a cost center, which doesn’t help convince executives to prioritize allocating budgets to physical security over another department that proposes to increase revenues, profits or their competitive position. Physical leaders need to change their engagement model with the rest of the organization to be successful.

Convergence Is Broader Than Physical Interaction Between Cybersecurity and IT

Executives have become more data driven and tend to support stakeholders that provide clear visibility, supporting metrics and relevance to core mandate success; as a result, along with stakeholders, they’ve developed a general consensus about how various departments engage – culturally, collaboratively and how they support one another and communicate these aspects. Focusing only on how executives and stakeholders can help approve project funding or respective requirements is an increasingly losing battle.

Stakeholders have transitioned from only focusing on program-level challenges to incorporating convergence, interoperability and business operational improvements as critical success components of key initiatives. Despite the significant advances in technology that have the potential to reshape part of a physical security program, making commitments to specific technologies or integration plans irrespective of identifying which initiatives to align with and prioritized business risks to help remediate is likely to result in choices that aren’t optimized to support executive mandates.

In the process, corporate governance and cybersecurity have matured, arguably much further than they have within physical security. Most other departments adopted corporate policies for cybersecurity, privacy and compliance while embracing the same risk management framework the C-suite uses to make such decisions.

The rest of the organization continues to evolve a common operating model, and physical security leaders have a choice as to whether they want to push harder with their existing model or forge ahead transitioning to one that is proving to be more successful for other stakeholders.

If convergence was only about integrating with other technical or security domains, then the rest of the enterprise has already done this, and physical security is late to the party.

Stakeholder Success Creates Unique Pressure for Corporate Security

Increased success in how stakeholders navigate key initiatives reinforces executives’ confidence in the feasibility of their mandates and influences expectations of how all stakeholders should successfully respond. A culture develops around principles that are applied, innovations employed and how they’re communicated. Conversely, stakeholders that don’t engage or successfully participate in this model become less visible.

Security Leaders Have Unique Challenges

Security leaders have a disproportionate challenge that distinguishes them from other stakeholders. In most cases, security isn’t going to propose generating revenue since many aspects of security are difficult or nearly impossible to quantify (life safety in terms of occurrence and dollar values).

An Unavoidable Blueprint for Success

There exist successful examples across an organization that one can learn from. Physical security has witnessed InfoSec move from the basement to the board room, demonstrating that challenges unique to security can be overcome by balancing the desired security program and technology improvements while successfully participating in the broader organizational environment to gain support for security improvements that they want to make, get funding approved and support their efforts.

The success of the CISO has paved the way for executives to develop specific expectations of what a risk discussion sounds like, what a security briefing looks like, how a business proposal is composed and how these are critical elements of initiatives that support core mandates and need to be supported.

When physical security leaders employ a different approach within an organization where the CISO has been successful, it causes a disconnect in contrast to expectation. For example, executives often wonder “if physical and information security are both security domains, why do they often subscribe to entirely different sets of principles?”

- Why are similar technologies not subject to the same standards and guidelines?

- Why aren’t physical security systems being assessed by the same auditors?

- Why are the risk metrics being presented not the same ones used by everyone else?

These aspects are often confusing to executives and aren’t going to spend much effort rationalizing an answer. Rather, executives will just take a pass. Physical security could consider remediating these areas by observing the lessons of the CISO’s journey (which was very intentional) and adopting some of their successful practices.

- How do they overcome quantifying security risks? What measurements are used?

- How do they successfully engage stakeholders to become part of key initiatives?

- How do they best communicate security issues in executive terms and align with boardroom-level concerns?

Convergence Redefined

<name=”technology”>

Environment Shapes How Convergence Is Defined

More than ever, physical security leaders need to be more engaged and get more creative. In many cases, convergence is emerging as the answer; however, since each organization determines their objectives independently from one another, risk profiles vary and how they’re staffed and cultural, political and interpersonal dynamics differ, successfully engaging across the

For these reasons, convergence is repeatable framework rather than a specific “thing” that is implemented. Internal dynamics shape how convergence is defined, while convergence shapes the manner in which we may respond to evolving business, risk and security demands.Anatomy of Convergence

Convergence as a concept isn’t static – it will continue to evolve – but is robustly anchored to four core pillars (which will be discussed later on in the paper along with best practice recommendations).

Technology

Technology is a requisite component to facilitate most desired outcomes in the modern business environment; however, convergence is defined neither by specific technologies nor the integration between them. Integration has been occurring within physical security for decades, and some elements of these efforts may or may not qualify as convergence efforts but are not as a whole based on that single criterion. Failure for physical security practitioners to recognize this may result in misdirection opportunity, resources and impact.

The industry is entering an era where technology innovations are not just iterations but rather generational leaps. Unlike in the past, a considerable portion of advancements infuse innovations from outside physical security that completely change the paradigm to solve longstanding challenges that have persisted from the past and inform how we can tackle opportunities more efficiently in the future.

Practitioners will encounter technology that is credibly asserted to be better or faster or has more features, but it’s critical to observe that these conclusions are in isolation from the context in which they are best applied. It could easily be argued that a technology that is inferior but has more relevant attributes to fuse logic layers, streamline processes and assimilate data into relevant insights and actionable outcomes for a key initiative that is more compelling.

Business Acumen

Between events that occur daily, persistent threats, systems and people to manage, security leaders have a lot on their plates. Often when knowing what needs to be fixed, improved or better resourced, it can be too easy to fall into a pattern of requesting support from executives that overlooks how we engage with the rest of the organization, which largely doesn’t think about security or think about it in the same way.

Organizations are made up of people who have unique viewpoints, backgrounds and specializations. No matter how great ideas may be, building successful dialogue and support is essential. It requires an understanding of a stakeholder’s business, environment, processes and challenges while often being able to communicate effectively in nonsecurity terms. These aspects are often a combination of adjusting interpersonal behavior and seeking aspects that are regarded in the organization’s culture – such as business templates, processes, methodologies, metrics and governance practices.

Physical security leaders need to assimilate the priorities of the greater organization into their own objectives to achieve greater relevance and support from other stakeholders. For many, this will mean shifting from relationships with others in the capacity of “approvers” of the elements of projects security is working on to being collaborators with stakeholders in solving organizational initiatives together.

Risk

In a perfect world, all security deficiencies would be funded; however, executives know that if they funded all security deficiencies, their organizations wouldn’t be profitable. They have limited resources, most of which are going to be allocated to executing key initiatives. Ultimately, executives know they need to take many risks.

Too often, physical security culture speaks of risk in colloquial terms, interchanging security events as “risks.” A security event may become a risk, and it may not.

Often, the context around an event’s occurrence shapes what aspect of the business is affected and to what extent the impact. It’s the latter part that is risk, which is what executives want to discuss. This is really important, since most organizations have formal frameworks for identifying, evaluating and measuring risk, which is much broader than security, ranging from risks within their markets to supply chain, sales, innovation and more. Generally, the bottom line that executives want to know is – “What’s the impact of not funding specific risk item?” so they can determine if they have the appetite for doing so. The risk framework they employ will give them the information they require in familiar terms. If physical security leaders aren’t subscribing to the same framework and presenting security events (even if they are critical), odds are that executives don’t have the tools to properly consider (or appreciate) what is being presented. Integrating the organization’s risk framework into the physical security practice is also critical for physical security leaders to properly understand risks that exist across the organization and how they’re prioritized and demystify what’s likely to get funded (and consider participating in those).

Governance

Broadly speaking, governance is how an organization manages its obligations, defines its execution and attains reliability and insight into its performance. Obligations can range from external forces (e.g., regulatory compliance) to internal forces (specific measures the organization believes it needs to regulate to operate effectively).

Policies, practices and controls are just some areas many may find familiar.

While cybersecurity has gained considerable awareness in the physical security industry, “governance” hasn’t but is arguably even more important. How can security ever be better than an organization’s ability to govern it?

Even for security practitioners who aren’t planning to undertake convergence as a practice, preparing for the modern threat landscape necessitates collaboration

between people, departments, systems and intelligence. Formalizing ways that data can be shared and secured, maintain integrity and comply with privacy requires that the different stakeholders working together adopt common practices.

Convergence will require physical security to observe the governance structure of the organization and its implementation within various departments and harmonize (if not adopt) with physical security. Collaboration across the organization can’t be successful with stakeholders subscribing to different principles and methodologies and conflicting policies. Without alignment, there won’t be trust, consistency or acceptable oversight, and many projects will be unable to get off the ground.

Engagement

Convergence is generally working across at least two of the four pillars. Most modern projects and technologies will require it anyhow. Many examples exist: Implementing mobile identity/credential solutions will require participation from IT, IT operations, InfoSec and governance (privacy, audit) at minimum just to allow the app to be installed, rolled out and serviced – additional layers get added if physical identity lifecycle gets integrated with IT’s process.

OT inherently requires domain expertise across a broad spectrum to even entertain modifications, upgrades and weighing risks associated with all those choices – from people who know the old system to those who understand the existing process and desired changes. This expands to include multiple security and risk professionals to assess the various physical, digital and analog attributes and associated risk.

For some, much of this will be familiar. For others, it may seem as if convergence is an unstructured alphabet soup of the day. While it does take some getting used to, once security leaders are plugged into the various elements discussed in this paper, working within the framework isn’t a heavy lift.

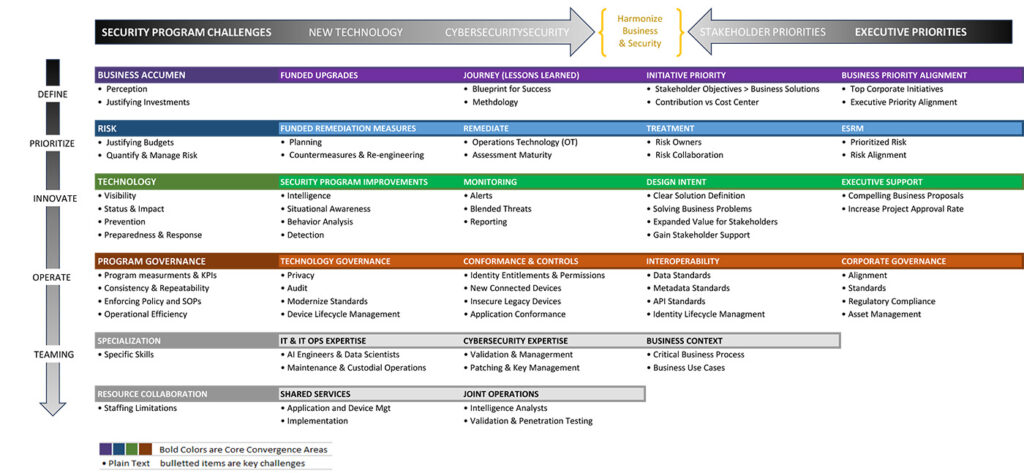

Figure A: Overview of Convergence as a Framework

Security programs have their own core challenges and objectives (far-left column). Security leaders seek solutions via innovation (second column from left) but have specific increasing obligations such as cybersecurity (third column) from left).

Meanwhile, these activities can’t be undertaken successfully in a silo. Leaders need to consider how their program objectives converge with organizational mandates and initiatives from executives (far right) and stakeholders (second from right).

The flow from the left (security) intersects with the inward flow from the right (business side) to align security objectives with the concerns of the business.

The four core pillars of convergence (illustrated as horizontal purple, blue, green and red headings) are key areas of intersection between solving specific security leadership challenges (all regular text bulleted items in the matrix) in the respective area of consideration (from the highest order of the organization to program level, top and downward).

Range of Outcomes

The purpose of convergence is for security practitioners to be more successful. How will proactively undertaking convergence improve security programs and experience of practitioners?

-

- Working across the decision-maker spectrum to understand their priorities and partner in their success changes the perception of

- Align security projects to deliver more value to stakeholders, increasing the likelihood for funding.

- Solve new and inherent security challenges through innovative approaches, new methods and practices.

- Building credibility with stakeholders to gain access to specialized resources (cyber, IT, audit, AI, etc.)

- Building partnerships to eliminate the need for duplicative resources to operate or maintain systems.

Technology: Navigating Unprecedented Opportunity and Complexity

The physical security industry has undergone three major technology paradigm shifts throughout its history. This section reviews the latest paradigm shift in key areas of technology within the physical industry, advantages they bring, considerations and how convergence is applicable (if not requisite) for success, not to lose sight of existing technology which needs to be addressed, ranging from legacy to current, that may be insecure or conflict with InfoSec policy.

Industry Snapshot: Three Technology Paradigm Shifts From Mechanical Apparatus to Electronic Systems

This shift ushered in a different range of controls to monitor, interact and react to specific environment states or events in different ways, but mainly the ability to specify and scale and add consistency due to less reliance on humans which were needed to perform all functions through presence, observation and enforcement.

Hello World: IP-Enabled Devices and Systems

The next shift occurred when the industry eventually embraced network-enabling systems and devices. This shift led to a variety of operational and financial benefits by enabling technology to join a digital community, enabling systems to communicate with one another, facilitating remote management, centralizing logs data and reporting and delivering alerts from one device to some other interface in a different location, and also facilitated centralizing systems, consolidating databases and infrastructure, where many users could share access (as opposed to servers in each location that could only be accessed at that location).

Modality and Logic

The current wave represents technology that is fairly diverse but is best summed up by two concepts: First, newer modalities in terms of where they deploy or exist in different ways that provide more advantages, such as cloud, mobile and virtualization, and second, newer technology that specializes in greater visibility, deeper intelligence and increased logic (e.g., AI, machine learning, automations).

In reality, both areas are seldom isolated from one another, and combined they result in a superset application – for example, an anomaly detection system in the cloud that analyzes system logs, virtual identity and user mobile telemetry data to analyze user behavior against specific controls and in turn producing alerts and automated response actions).

Ripple Effect

Each paradigm shift represented significant opportunities but also substantial challenges that set the stage for the industry to work through in subsequent years.

It’s not a bad thing, and not even a situation unique to physical security; nevertheless, it’s a reality that must be confronted.

The major paradigm shifts generally take root in the physical security industry borrowing technology innovated and being adopted in other domains, none of which the physical security industry are experts previously. While the industry embarks on adopting AI, it’s still getting its arms around encryption, properly securing IP devices or adequately managing them (status, patching, asset class, etc.).

Everything Looks a Lot Like IT

A couple of decades ago, physical security systems were fairly siloed from other departments and in most cases other systems within their own programs. Forward another decade, integration between physical security systems became more common, but systems were still fairly closed, commonly proprietary, with limited APIs and a range of other deficiencies that were common in IT systems.

In recent years, many aspects have improved. In fact, they had to as a prerequisite to even consider adopting the recent innovations. Imagine an intelligence project that needs data from a system that has no APIs to get the data out effectively (hint: limited data = limited insights)?

In fact, most of the improvements that have been iterating aren’t novel but are things that IT systems already had already incorporated as common practice. It’s hard to see, because it wasn’t any single thing or event, but physical security systems came to look very similar to IT systems. Aside from their application (how they are applied and the environment in which they are used, i.e., “purpose”), modern physical security systems are nearly indistinguishable from those in IT.

Considering the challenges the industry has had with the backside of adopting new technology, having an IT system profile both places a specific burden on physical security professionals but also eliminates quite a bit of ambiguity about what the appropriate response needs to be.

Cybersecurity in Physical Security

As the attack surface expands for new technology being considered, existing nonconformant implementations will easily get flagged by IT, InfoSec and auditors in the normal course of transparency, planning or collaboration of resources to better sustain environment.

It’s in the realm of impossibility that IT and InfoSec will adopt physical security’s policies and practices to make their own in reconciling these types of variances. IT ops and cybersecurity have spent years refining their approaches, establishing best practices and gaining the type of maturity that physical security should have already possessed; however, cybersecurity requires specific skills, and there are several areas within it that require deep expertise. For example, professionals that specialize in network security generally aren’t application security engineers, and neither are cryptographers penetration testers. For these reasons, many physical security leaders are overwhelmed by the pressure of meeting cybersecurity measures. But it’s for those very same reasons leaders don’t have to go it alone and should be looking to partner with existing specialized resources within their organizations rather than tasking physical security staff to spend years on becoming cybersecurity experts (because this is really what it takes). Other departments have demonstrated that they can work through similar pressures and transition toward having these functions become more of a central shared service model that can be relied upon (even shift such responsibility to) and get out of the business of running a parallel duplicative set of functions.

While new technology presents opportunity and a new set of challenges, the physical security industry will need to also reckon with challenges regarding their existing environments, some of which might be more recent investments that need to be brought into compliance, while others may be older and make doing so not feasible or even possible.

It’s in the realm of impossibility that IT and InfoSec will adopt physical security’s policies and practices to make their own in reconciling these types of variances. IT ops and cybersecurity have spent years refining their approaches, establishing best practices and gaining the type of maturity that physical security should have already possessed; however, cybersecurity requires specific skills, and there are several areas within it that require deep expertise. For example, professionals that specialize in network security generally aren’t application security engineers, and neither are cryptographers penetration testers. For these reasons, many physical security leaders are overwhelmed by the pressure of meeting cybersecurity measures. But it’s for those very same reasons leaders don’t have to go it alone and should be looking to partner with existing specialized resources within their organizations rather than tasking physical security staff to spend years on becoming cybersecurity experts (because this is really what it takes). Other departments have demonstrated that they can work through similar pressures and transition toward having these functions become more of a central shared service model that can be relied upon (even shift such responsibility to) and get out of the business of running a parallel duplicative set of functions.

While new technology presents opportunity and a new set of challenges, the physical security industry will need to also reckon with challenges regarding their existing environments, some of which might be more recent investments that need to be brought into compliance, while others may be older and make doing so not feasible or even possible.

Convergence Best Practices for Physical Cybersecurity

Too often recommendations are oversimplified to “work closely with IT to address cybersecurity,” but it would be misleading to infer that this was either the first step or adequate in scope. The reality is that IT has applicable scope that intersects with cybersecurity, InfoSec sits squarely in the middle of it, yet neither of them addresses the complete picture.

Ultimately, end users are responsible for what’s selected, what’s installed and the impact that may result within their environment – regardless of the actions of other parties. This nis why physical security leaders need to devise a plan to increase cybersecurity maturity throughout their selection process, requirements, design, valuation of proper configuration, regular audits and periodic penetration testing.

Physical security end users won’t become experts in cybersecurity; neither will their integrators. It’s too deep, there are too many specializations within, and would be duplicative to those resources that already exist on the InfoSec side of the organization. Convergence is the most efficient, effective and reasonable way to achieve this.

Align Cybersecurity Principles and Policy

The core objectives of physical and cybersecurity are quite similar. While specific scope, context, and application may be different, the core principles really shouldn’t be. Concerning systems, cybersecurity has a great deal more maturity and specialization in developing effective policy than physical security. Therefore,

physical security should seek all InfoSec policies and embrace them as their own — if the device is electronic, it should be in scope.

Engage Auditors Where Possible

InfoSec can only help with remedies based on what’s presented to them or they test for themselves. Unfortunately, physical security experts aren’t cybercity experts and often can’t adequately identify what should be put forward for consideration nor does it make sense for InfoSec to test everything.

Rather, physical security should first seek to understand ALL of the nonconformities (against organizational cybersecurity policies). Auditors, who are commonly separated from IT and InfoSec’s reporting structure (for good reason), independently perform this specific role in nearly every other part of an organization. In fact, it’s likely to happen in the future anyhow so it’s best to involve them early to help them acclimate to looking at physical security the right way. While they won’t be familiar with physical systems, they will know what to look for concerning conformance to specific policy and regulatory obligations.

Partner With InfoSec

Keeping in mind that audit compliance is well intended, but being compliant means just that, not necessarily that it goes far enough. Work closely with InfoSec in reviewing audit findings, areas of noncompliance and potential remedies. In addition, critical applications and devices should undergo further review, potential testing and threat modeling for selective consideration.

Engage IT

Some remedies and improvements will require IT’s assistance, while for others they can offer advice. Very little of this is new to them, as they’ve already worked

through these same issues in their own environments and have developed repeatable and scalable operations, which should be the goal versus ad hoc solutions for each issue, device or application. IT is also going to be in the middle initiative that supports different departments and will have insight into how internal standards are developing so being interoperable with others tomorrow is more likely and sustainable.

Be Aware of Specialization

IT is often thought of this all-inclusive umbrella, but it isn’t. Physical security should endeavor to identify who in IT to engage for productive conversations. For example, those that specialize in networking are completely different than those making decisions about password management mechanisms. While identity and access management specialists would be appropriate on technical matters, a project could also require nontechnical stakeholders who may own the identity itself (in some cases, HR).

Similar considerations exist on the InfoSec front. There are several specializations within the InfoSec domain in which it takes years to become an expert. Being an expert in one area doesn’t translate to having requisite knowledge in another area to provide sound advice. For example, it wouldn’t be appropriate to solicit advice from a network security specialist regarding application security. For the latter, an application security specialist should be engaged. The same goes for encryption matters (cryptographers) and so on.

Evaluate Risk

Physical security leaders must commit to moving away from practices that don’t incorporate system integrity and cybersecurity by design. While it’s impossible to secure everything to the degree desired, decisions should be made using an enterprise security risk management (ESRM) (CH 6) model – not by estimating based on past experience or occurrence.

Perform Validation

The bulk of deployments within physical security will continue to be performed by integrators who are indispensable for their expertise – getting these applications and devices to do what is intended – but they too are in a similar learning curve regarding cybersecurity. While they have the best intentions, end users should consider a process to inspect every deployment for conformance with cybersecurity policy and practices.

It might not be feasible to inspect all work at scale in all locations. This is where partnering with IT and InfoSec is critical to consider using the same methodology and tools they employ for the same purposes – by implementing specific controls (limiting access or what settings can be performed), using automated remote auditing to detect noncompliance and even spot checking some devices in some locations.

Global Sourcing and Procurement

Another area where physical security hasn’t been well integrated is how they work with purchasing and global sourcing departments. Physical security often partners with purchasing but using different sets of requirements and contracts than what others use, which often leads to certain nonconformities, vulnerabilities and nonstandard technologies making their way into the program in the first place.

In addition, physical security should partner with global sourcing and legal to ensure that contracts evolve to reflect the desired supported validation process for work to be signed off, handling for vulnerabilities that are discovered and paths for remedy so it doesn’t become a problem that persists throughout the rest of the application’s life. The simplest manner to achieve this is to not be separate from IT and InfoSec in these relationships, or at least to try to use the same contracts to address similar topics as they do. Some procurement departments are so large and so isolated from one another in the same organization that they aren’t aware that another person in their group interfaces with InfoSec with a different set of contracts than how they work with physical security — overlooking the common interests.

Enlist Resources

There already exist multiple IT and InfoSec functions within most organizations that perform all these aspects on behalf of nearly all other departments. Physical security leaders should ask themselves if owning these challenges is core to their charter and success or a distraction which is better served by experts already equipped to do so.

Business Acumen

Putting Physical Security Into Organizational Context Is Critical

All organizations have limited resources; therefore, it’s not possible to fund the majority of requests for investment. Executive management will generally only fund either what is critical to achieving their core business objectives or risks where the impact exceeds their appetite to defer addressing them (and suffer the consequence). It’s increasingly important to demonstrate that security and business objectives are relevant and should coexist.

Changing Perception

The perception of departments within an organization is highly correlated to the nature of their business function and contributions to organizational objectives. For example, a major manufacturing facility that produces a product that makes up a large share of revenue is quite obvious. Conversely, security isn’t as straightforward, as its core function doesn’t generate revenue, impact competitive market position or serve as a primary source for increasing profitability (again, core charter, perception, etc.).

Often Measured Incorrectly and Perceived as a Cost Center

Aligning with stakeholders from departments that are closer to the direct contribution model changes the visibility and perception of how others see security. Too often, physical security is siloed on the outer edges of this model, leading to the perception that it’s a cost center, a part of real estate or a bundle of facility “assets.” This frequently leads to being structured to report into a similarly perceived business function (real estate, facilities, etc.). The downside is then physical security is often measured by those same departmental metrics, such as cost + value of services delivered per square foot. The result is significant incentive for nonsecurity management to endeavor setting cost containment objectives to improve these metrics, which aren’t even remotely aligned with security objectives. Additionally, real estate management executives too often won’t prioritize security objectives if they jeopardize said metrics.

Solution vs. Tactical

As compelling as technology has become, the era within physical security end- user environments won’t be defined by security being better, faster or more feature rich. Rather, how intimately we understand the challenges and selectively infuse innovations to improve outcomes ultimately changes the paradigm for end users.

Recent technical advances represent unprecedented opportunities; however, the ones chosen to be pursued must correlate back to enabling the business’s core objectives and operate within a model used by the rest of the organization to gain greater support. Without this, security remains on the edges, unable to adequately influence support to execute.

Defining Returns on Investment (ROI)

Executives expect an effective business case. Too often, security leaders are able to demonstrate how their proposals will be cash flow positive, yet the majority of the time they still fail to get funding. Executives already have detailed plans to increase top and bottom lines. For example, if the chief financial officer has committed goals to increase profits by $200 million, cobbling this together across dozens of projects isn’t desirable – too many projects, resources spread thin and not core to their business.

Rather, they primarily want to know if what’s being proposed is absolutely essential. In more direct terms, “can I afford to NOT fund what’s being proposed?” If the answer is “yes,” funding is unlikely (at least this time around). If the answer is “no” then regardless of ROI, budgets get moved around to provide appropriate support. ROI adds sensibility to a story but can’t be the main theme. Security leaders need to tie into the success of executive’s core commitments.

Executives don’t endeavor to spend money on technology or security; rather, they invest in solutions where success has a major dependency on the technology being proposed. From this viewpoint, executives that approve of budgets, technology and security are respectively the technical components of solutions achieving solutions and mitigating risk.

Leading Organizational Drivers

While business fundamentals remain constant, how executives chart a strategic course to execute changes based on markets and business environments evolves. The following section outlines contemporary drivers that are defining key initiatives where physical security is increasingly requested to participate with other stakeholders or represents an opportunity to do so.

Summary of Best Practices for Business Assimilation

Identify the Organizational Landscape

- What are the CEO’s top three mandates?

- Who are key stakeholders?

- What are each stakeholder’s top initiatives?

Determine Relevance, Role and Critical Nature Within Prioritized Initiatives

- Do they have any physical security components?

- Have these been assessed and determined without engaging physical security?

- What additional value and impact can physical security have to achieve desired outcomes?

Develop Common Incentives

- Assimilate the needs of security to align with the established business goals of the organization.

- Convey the indispensable role of physical security’s needs to the success of business goal.

- Can the business afford NOT to approve physical security’s proposal?

Reevaluate Reporting Structure

- What are the specific success metrics for physical security? Can they be quantified?

- Do they accurately represent physical security’s charter or someone else’s?

- Does current reporting structure facilitate or present a barrier to a success model?

Build Alliances and Borrow Pages of Others’ Playbooks

- Build relationships with key stakeholders, not for one project but rather ongoing as the plan for them.

- Explore if there exists another risk domain which already uses the correct measurement of success.

- Learn, borrow and adopt successful models from other departments.

Converging Perspectives About Risk and Security

Let’s face it – security only exists to mitigate specified risks. Good risk management requires a proven and effective methodology to assess, determine and manage. It’s also critical to be able to be able to communicate the scope, criticality and potential remedy of risks to different constituents within the organization to gain support.

Just as physical security generally practices tiering of different types of facilities and access points pertaining to their critical nature and using as a basis for relevant guidance, the greater organization also has well-established guidance mechanisms for risk guidance. It’s generally used for all business facing functions to make decisions. However, too often, physical security doesn’t observe it (or aware of its existence) which leads to lack of proper classification, relevance and context of security concerns being presented – and more often than not being declined for funding. This section will review how physical security converges with how the rest of the organization practices risk and how to participate and achieve greater success in moving security concerns forward.

According to Helen Negre, chief cybersecurity officer at Siemens USA, “Siemens is a high-collaboration, high-communication environment, and that feeds into everything we do, including risk management. Risk is not something hidden or siloed – it’s discussed across all areas of our organization. You cannot have true enterprise risk management without evaluating risk across the entire enterprise and having a response strategy that includes reduction, transference and avoidance efforts that take the entire organization into account.”

Organizational Mindset

Executives responsible for approving security funding generally entertain remediating dozens or even hundreds of risks, yet they only have resources to approve a fraction of them. When proposed investments fail to impress executives as to whether they are required to execute strategic objectives, they often decline, no matter the asserted ROI. The exception is for risks that executives can’t afford NOT to approve (because the impact of the risk occurring is far greater than their appetite to carry the risk). It’s those stakeholders who can communicate most effectively with decision makers on their terms that are more inclined to get funding. Most risk owners in an organization aren’t within the security domain but are able to place risk in a business context within a framework that executives use and expect.

Executives are accustomed to how these conversations play out with stakeholders and are looking for a very specific exchange of information. When physical security proposes budgets for program improvements, increased preparedness or event mitigations without converting them into the same metrics that everyone else uses, it’s effectively two different conversations about the same thing.

Prioritizing Focus Around Risk Makes Sense to Achieve Security Objectives

For years, physical security had been able to manage risks within their program inside an opaque wall – part art of this has been that some aspects of physical security are difficult to quantify, and to some extent the culture of operating as a silo apart from other business units (BUs) and risk functions was pervasive. However, with increased pressure on OpEx budgets and CapEx requests, this approach just isn’t sustainable, and physical security needs to embrace the same risk practices as the rest of the organization to be viewed as a relevant risk stakeholder – not just as security experts.

Organizations need experts who look at their environment from a security perspective, but they need to contemporaneously see security in context of risk and be able to communicate this effectively to the rest of the organization while surrendering to the fact that most decisions are made outside of the security domain.

Converging Language and Practices to Work Together (Methodology)

Most organizations have established and employ risk management frameworks. While maturity of actual implementation between organizations may vary, these frameworks are generally based on published standards and share core elements (for example, ISO 310000:2018 focuses on the principles, process and integrating risk across an organization, while IEC 31010:2019 dives deeper into specific techniques for assessment, risk management and decision making.).

Unfortunately, most physical security leaders haven’t yet redesigned their approach to risk around these standards and have only marginally aligned practices to those of their internal stakeholder peers. As a result, there are significant gaps between how groups would assess, interpret, quantify and make decisions about the same risk. The transition can be daunting for many physical security leaders, ranging from upending entrenched practices to trepidation about how to design such a new approach. The good news is physical security doesn’t need to reinvent how to do this on its own. Rather, the process is about discovery of what practices have already been established and are in use and engaging with others internally that employ them – convergence of people and process to get there.

Convergence of Cultures

This journey will require a significant adjustment for most physical security leaders: not only embracing a new model, but trickling down into how remediation measures are prioritized, controls are purposely designed and various operational areas are adapted.

Practices

Risks that don’t involve security elements do exist throughout the organization, which is why there’s a broad risk framework that can be used by all stakeholders across the organization, including security. Frameworks generally entail practices that are repeatable, scalable and employable regardless of business unit, which helps all participants collaborate on multifaceted risk, understand the potential impact and accurately consider the context of the property treatment.

Structure

Most risks have owners but have many elements that require participation of various expert resources to properly assess and design appropriate remedies. For collaboration across various disciplines that report into different business units (and not have concerns stuck within a specific BU), a specific risk program management structure needs to be employed through committees, dotted-line reporting and procedures to enable appropriate visibility, progression and handling.

Language

Not to be underestimated, adoption of common practices across a broad spectrum of business disciplines (within a committee structure) requires a common language. Using common references from one discipline might not be well understood by the rest of the participants or be best suited to be applied within a diverse group.

Guidance

Ultimately, the goal for a security leader should be to reduce risk that is determined

to be undesirable for the organization and in turn gain support for adequate resources to execute. In the increasingly complex business environment and evolving threat landscape, employing a risk-reduction strategy is required.

However, when a security leader’s objective is to gain support for addressing specific risks, the core focus should be on determining if the business can afford to NOT support the proposed treatment. If the answer is any variation of “yes,” then unless it’s packaged under another initiative that had the opposite answer, it’s unlikely that support will be provided. There are steps physical security practitioners can take.

Become a Critical Component of Funded Risk

Funded risk exists somewhere in the rest of the organization. Often, physical security functions are components of the treatment, but it is poorly defined, inaccurate and not disclosed to physical security. Don’t assume these are being quantified and specified correctly.

Physical security leaders need to engage proactively with other risk owners, identify risks that are likely to have higher ratings and help define treatments which include physical security measures that reduce residual risk metrics (improve projected outcomes).

Obtain Documentation

Seek and collect all information regarding the ESRM program employed within the organization. Identify and familiarize the organizational risk classification model, governance structure and decision-making process.

Adopt and Adapt

Security leaders need to embrace how the rest of the organization thinks about risk – and work with them. Bridging the gap between physical security culture and practices and how the rest of the organization makes risk-based decisions requires adopting their frameworks and processes.

Find Mentors

Reach out to stakeholders about their journeys – everyone has gone through some transformation to use the same methodology from where they were prior.

Revise Risk Perspectives

If not already using an ESRM model, reassess the currently employed methodology on how physical security defines, documents and managed risk. Ensure that risk management is bifurcated from event response and the standard operating procedure (SOP) process.

Meet With Stakeholders

Generally, risk owners will be either stakeholders or those designated by them. Note the difference between technical “requirement approvers” and risk owners – seldom are they the same.

Brief Direct Management

Brief direct management about changes that need to be made regarding risk management, how this impacts existing program priorities and where their support is needed.

Meet With the Chief Risk Officer

While well versed in risk, the chief risk officer (CRO) might not completely understand the scope of physical security and some of the unique aspects that accompany it.

The objective here is not to advocate any specific risks but rather to get their advice in ramping up participation in ESRM and gain their support in navigating obstacles commonly presented to physical security leaders that don’t report directly into a risk function.

There’s quite a bit CROs can do – they are executives and are accustomed to meeting with senior executives to create common incentive models and dotted lines that can’t be ignored by direct reports which have competing objectives or metrics. In fact, this is a top priority for a CRO, so there should be common ground.

Waivers

If waivers are implemented in the organization’s risk framework, investigate the criteria for how durations are assigned. Revisit past proposals which requested support for risk remediation that were declined. Seek documentation as to whether a waiver was provided or reasons why they weren’t – this could be due to misclassification of risk or process not being followed. Attempt to get waivers mapped to them in retrospect or be prepared to request a waiver the next time they’re proposed and deferred.

Stay Engaged

Sometimes security can feel like good security isn’t a priority for the rest of the organization, but through these measures practitioners will find a broad community that is passionate about risk. Now knowing how to leverage risk to prioritize and improve security outcomes, consider getting involved on committees to establish physical security leadership as a peer and help shape the process (and perhaps more influence to implement the waiver if they aren’t already).

Governance

Governance is generally thought of as oversight, but it has broader meaning and application including the structures, processes and practices in place to ensure execution and accountability. From a security standpoint, these are critical mechanisms to ensure that expectations are defined, managed and executed.

- Implement decision-making authorities, decision processes and

- Program charter, goals and core principles

- Ensure that obligations are managed and achieved (regulatory, third parties, )

- Create and oversee methodologies, practices and policies

- Processes to validate implementation measure performance against intended results

- Facilitate improvement and corrective action for noncompliance

Critical Context for Physical Security

A key concept of convergence is the ability for various business functions that possess different domain expertise to work together to achieve better outcomes. This paper has underscored the functional areas where this occurs: technology, risk and assimilating these aspects into the business both beyond and inclusive of physical security departmental interests.

While cybersecurity has gained recognition across the physical security industry as a top priority to reconcile, governance hasn’t made the headlines. However, for the rest of the organization, governance arguably has higher billing than cybersecurity since executives recognize that the two are inextricably linked and cybersecurity can never be better than their ability to govern it. Good governance is necessary for good security.

Confusion Between Governance and Compliance

Whereas governance is focused internally on unique circumstances (“what should we do”), compliance measures are due to an external mandate resulting in having to meet a specific criterion (“what must we do”) such as industry and regulatory requirements. They definitely intersect, and the key is devising solutions that incorporate both. For example, meeting a compliance item might satisfy a regulatory obligation item but likely doesn’t go far enough to adequately remedy a specific risk or scope of risks in that environment. Most compliance measures are specific for an industry and designed as the lowest common denominator to ensure most that need to comply find it feasible to do so.

Translation: contrary to broad perception, compliance is really the minimum – not the end state. It’s up to the organization to look at the bigger picture across all regulatory obligations, risks and business considerations to formulate the best policies, controls and plans that meet all commitments and program goals holistically.

Key Transition Areas

IT has long subscribed to an IT governance model where all organization regulatory and organizational commitments are documented, crossmapped, performed and audited. Conversely, most physical security programs haven’t yet instituted a formal and comprehensive governance program and largely distribute some of these responsibilities across practice areas or teams.

Evidence of this is such that physical security programs that formalize governance programs tend to cover the same areas of their IT counterparts and consider very similar standards around systems, security, audits, validation, etc. Many of the common practices within physical security wouldn’t be compliant using the same metrics, and prioritizing cybersecurity would have come much sooner.

Interpreting what is secure, why and what approaches would be acceptable is based on core principles that shouldn’t vary between the physical and IT realms. How things might be executed may vary due to circumstance (application, resources, feasibility, etc.), but perspective, assessment methodologies and decision making should be the same. The fact that for so long that they haven’t been is arguably the root of the delay of cybersecurity consideration and the connective tissue for all aspects of convergence. For these reasons, many physical security leaders are advised to implement or reengineer their governance programs to incorporate and align with those which already exist within IT and InfoSec and across the organization. They should avoid redundancy and only be unique where an area of physical security requires further consideration to execute.

Best Practices for Governance Convergence

For many physical security leaders, prioritizing and building a formal governance program will be a significant shift in methodology, practice and skill sets; however, if leaders are expecting different results with respect to cybersecurity, intelligence outcomes and being accepted by their counters, it’s an inevitable journey.

Understand Organizational Commitments

- Meet with stakeholders outside of physical security.

- Gain insight into what specific regulatory compliance obligations the organization must meet.

- Perform a documented mapping between compliance items, controls and physical functions.

Partner With Internal Governance, Risk, Compliance (GRC) to Understand Their Framework

- Adopt all policies that currently don’t exist or would be redundant.